By Steve Bishop

(Disclaimer: The views expressed by guest authors do not necessarily reflect those of GodandMath.com. Guest articles are sought after for the purpose of bringing more diverse viewpoints to the topics of mathematics and theology. The point is to foster discussion. To this end respectful and constructive comments are highly encouraged.)

It has been said that the most incomprehensible thing about the world is its comprehensibility. Mathematics is only possible because God has created an ordered, law-full, universe that is comprehensible. Part of the task of mathematics is to describe the wonder of God’s good creation and thereby reveal some of the invisible attributes of God e.g. his faithfulness. Mathematics is also integral to the fulfilling of the creation mandate to open up and develop the creation. Mathematics is an important tool to help us steward and unfold the potentialities of the earth. Music, art, science and economics are four subjects that would be severely impoverished without the aid of mathematics.

Mathematics is a collective term for a number of related fields: arithmetic, geometry, topology, statistics, probability, … . All of which investigate and open up the two most basic aspects of reality: the numerical and spatial. (Applied mathematics also deals with a third aspect: the kinematic).

Math is a human activity therefore, it comes replete with human limitations: it is fallible, corrigible, culture- and value-laden. However, it is based in creation – it is not arbitrary or the product of social agreement. This is where a Christian view of math diverges from the social constructivist view. This Christian view of math does justice to both epistemological subjectivity and ontological objectivity.

Mathematics is based in created reality. It is not neutral; religious beliefs shape mathematical theories.

Mathematical Education Aims

Hence, mathematics education should:

1. Be placed in a historical and cultural context.

This will help to expose the myth of mathematical objectivity.

2. Be rooted in reality and everyday applications.

This will help show mathematics as a tool for unfolding and developing the creation.

3. Be integrated with other subjects.

Mathematics deals with the two most basic aspects of reality, the numerical and the spatial, these aspects are basic to all other curriculum subjects. The integration with other subjects, particularly science, reveals the role of mathematics as a tool to help fulfill the cultural mandate.

4. Describe the beauty and order of creation and to help students understand creation.

5. Reveal some of the attributes of God (Rom 1:20; Ps 19:1). Particularly the faithfulness of God to His creation exemplified in His laws and the lawfulness of creation. Without this mathematics would be impossible.

6. Enable us the be better stewards of God’s creation.

7. Provide fun and enjoyment.

8. Focus on understanding rather than rote or memorization.

9. Recognize that each student is created in God’s image and that each student is unique.

Differentiation will be important. We all learn in different ways and at different rates, this should be taken into account.

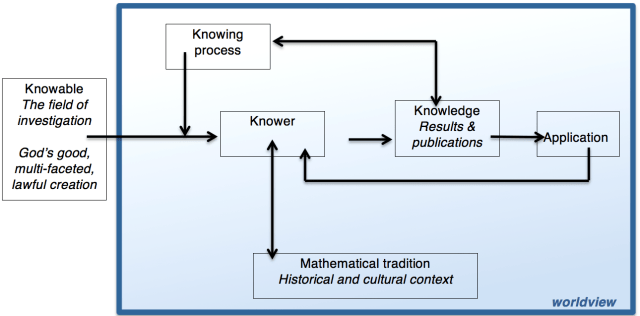

A model for mathematics – all activity takes place within a worldview. Hence epistemological subjectivity, but ontological objectivity. History and application play important roles (Adapted from an original diagram by Revd Richard Russell.)