by John D. Mays

Back in 1999 when I began teaching in a classical Christian school, one of the first books I heard about was James Nickel’s little jewel, Mathematics: Is God Silent? Must reading for every Christian math and science teacher, the book introduced me to a serious problem faced by unbelieving scientists and mathematicians. Stated succinctly, the problem is this: Mathematics, as a formal system, is an abstraction that resides in human minds. Outside our minds is the world out there, the objectively real world of planets, forests, diamonds, tomatoes and llamas. The world out there possesses such a deeply structured order that it can be modeled mathematically. So how is it that an abstract system of thought that resides in our minds can be used so successfully to model the behaviors of complex physical systems that reside outside of our minds?

For over a decade now this problem, and the answer to it provided by Christian theology, has been the subject of my lesson on the first day of school in my Advanced Precalculus class. But before jumping to resolving the problem we need to examine this mystery – which is actually three-fold – more closely.

In his book Nickel quotes several prominent scientists and mathematicians on this issue. In 1960, Eugene Wigner, winner of the 1963 Nobel Prize for Physics, wrote an essay entitled, “The Unreasonable Effectiveness of Mathematics in the Natural Sciences.” Wigner wrote:

The enormous usefulness of mathematics in the natural sciences is something bordering on the mysterious and…there is no rational explanation for it…It is not at all natural that ‘laws of nature’ exist, much less that man is able to discern them…It is difficult to avoid the impression that a miracle confronts us here…The miracle of appropriateness of the language of mathematics for the formulation of the laws of physics is a wonderful gift which we neither understand nor deserve.

Next Nickel quotes Albert Einstein on this subject. Einstein commented:

You find it surprising that I think of the comprehensibility of the world…as a miracle or an eternal mystery. But surely, a priori, one should expect the world to be chaotic, not to be grasped by thought in any way. One might (indeed one should) expect that the world evidence itself as lawful only so far as we grasp it in an orderly fashion. This would be a sort of order like the alphabetical order of words of a language. On the other hand, the kind of order created, for example, by Newton’s gravitational theory is of a very different character. Even if the axioms of the theory are posited by man, the success of such a procedure supposes in the objective world a high degree of order which we are in no way entitled to expect a priori.

One more key figure Nickel quotes is mathematician and author Morris Kline:

Finally, a study of mathematics and its contributions to the sciences exposes a deep question. Mathematics is man-made. The concepts, the broad ideas, the logical standards and methods of reasoning, and the ideals which have been steadfastly pursued for over two thousand years were fashioned by human beings. Yet with this product of his fallible mind man has surveyed spaces too vast for his imagination to encompass; he has predicted and shown how to control radio waves which none of our senses can perceive; and he has discovered particles too small to be seen with the most powerful microscope. Cold symbols and formulas completely at the disposition of man have enabled him to secure a portentous grip on the universe. Some explanation of this marvelous power is called for.

The first aspect of the problem these scientists are getting at is the fascinating fact that the natural world possesses a deep structure or order. And not just any order, mathematical order. It is sometimes difficult for people who have not considered this before to get why this is so bizarre. Simply put, the order we see in the cosmos is not what one would expect from a universe that started with a random colossal explosion blowing matter and energy everywhere.

Many commentators have written about this and professed bafflement over it. All of the above quotes from Nickel’s book and many, many more are included in Morris Kline’s important work, Mathematics: The Loss of Certainty, which explores this issue at length. In his book The Mind of God, Paul Davies, an avowed agnostic, prolific popular writer and physics professor, takes this issue as his starting point. Davies finds the order in the universe to be incontrovertible evidence that there is more “out there” than the mere physical world. There is some kind of transcendent reality that has imbued the Creation with its mathematical properties.

The second aspect to the problem or mystery we are exploring is that human beings just happen to have serious powers of mathematical thought. Now, although everyone is happy about this, I rarely find anyone who is shocked by it. Christians hold that we are made in the image of God, which explains our unique abilities such as the use of language, the production of art, the expression of love, self-awareness, and, of course, our ability to think in mathematical terms. Non-Christians don’t accept the doctrine of the imago Dei, but seem to think that our abilities can all be explained by the theory of natural selection.

But hold on here one minute. Doesn’t it seem strange that our colossal powers of mathematical imagination would have evolved by means of a mechanism that presumably helped us survive in a pre-industrial, pre-civilized environment? Our abilities seem to go orders of magnitude beyond what evolution would have granted us for survival.

I know all about the God-of-the-gaps argument, and I’m not going to fall for it here. It may be that some day the theory of common descent by natural selection will be able to explain how we became so smart. That’s fine, and I’m not threatened by it. All I’m saying is that for now Darwinism still has a lot of explaining to do. And getting back to the concerns in this essay, I for one do not take Man’s amazing intellectual powers for granted. They are wonderful.

The third aspect to our problem is the most provocative of all. Mathematics is a system of symbols and logic that exists inside of our heads, in our minds. But the physical world, with all of its order and structure, is an objective reality that is not inside our heads. So how is it that mathematical structures and equations that we dream up in our heads can correspond so closely to the law-like behavior of the independent physical world? There is simply no reason for there to be any correspondence at all. It’s no good saying, Well we all evolved together, so that’s why our thoughts match the behavior of reality. That doesn’t explain anything. Humans are a species confined since Creation to this planet. Why should we be able to determine the orbital rules for planets, the chemical composition of the sun, and the speed of light? I am not the only one amazed by this correspondence. All those Nobel Prize winners are amazed by it too, and they are a lot smarter than I am. This is a conundrum that cannot be dismissed. John Polkinghorne said it well in his Science and Creation: The Search for Understanding:

“We are so familiar with the fact that we can understand the world that most of the time we take it for granted. It is what makes science possible. Yet it could have been otherwise. The universe might have been a disorderly chaos rather than an orderly cosmos. Or it might have had a rationality which was inaccessible to us…There is a congruence between our minds and the universe, between the rationality experienced within and the rationality observed without. This extends not only to the mathematical articulation of fundamental theory but also to all those tacit acts of judgement, exercised with intuitive skill, which are equally indispensable to the scientific endeavor.” (Quoted in Alister McGrath, The Science of God.)

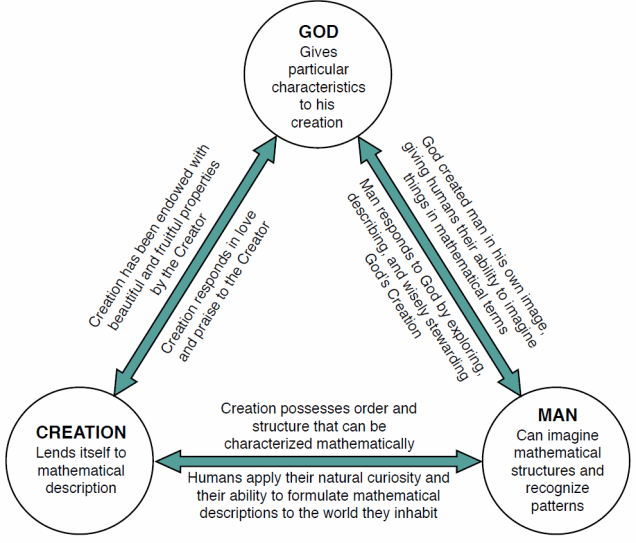

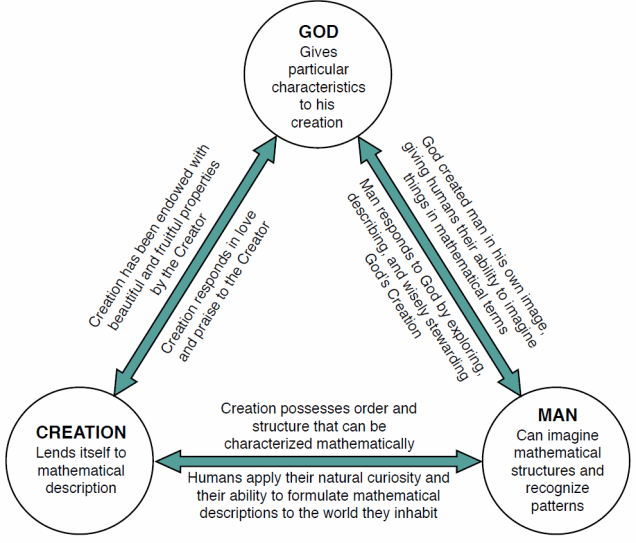

Which brings us to the striking explanatory power of Christian theology for addressing this mystery. As long as we ponder only two entities, nature and human beings, there is no resolution to the puzzle. But when we bring in a third entity, The Creator, the God who made all things, the mystery is readily explained. As the figure here indicates, God, the Creation, and Man form a triangle of interaction, each interacting in key ways with the other. God gives (present tense verb intentional) the Creation the beautiful, orderly character that lends itself so readily to mathematical description. And we should not fail to note here that the Creation responds, as Psalm 19 proclaims: “The heavens declare the glory of God.” (I have long thought that when the Pharisees told Jesus to silence his disciples at the entry to Jerusalem, and Jesus replied that if they were silent the very stones would cry out, he wasn’t speaking hyperbolically. Those stones might have cried out. They were perfectly capable of doing so had they been authorized to. But I digress.)

Similarly, God made Man in His own image so that we have the curiosity and imagination to explore and describe the world He made. We respond by exercising the stewardship over nature God charged us with, as well as by fulfilling the cultural mandate to develop human society to the uttermost, which includes art, literature, history, music, law, mathematics, science, and every other worthy endeavor.

Similarly, God made Man in His own image so that we have the curiosity and imagination to explore and describe the world He made. We respond by exercising the stewardship over nature God charged us with, as well as by fulfilling the cultural mandate to develop human society to the uttermost, which includes art, literature, history, music, law, mathematics, science, and every other worthy endeavor.

Finally, there is the pair of interactions that gave rise to the initial question of why math works: Nature with its properties and human beings with our mathematical imaginations. There is a perfect match here. The universe does not possess an order that is inaccessible to us, as Polkinghorne suggests it might have had. It has the kind of order that we can discover, comprehend and describe. What can we call this but a magnificent gift that defies description?

We should desire that our students would all know about this great correspondence God has set in place, and that considering it would help them grow in their faith and in their ability to defend it. Every student should be acquainted with the Christian account of why math works. I recommend that every Math Department review their curriculum and augment it where necessary to assure that their students know this story.

John D. Mays is the founder of Novare Science and Math in Austin, Texas. He also serves as Director of the Laser Optics Lab at Regents School of Austin. John entered the field of education in 1985 teaching Math in the public school system. Since then he has also taught Science and Math professionally in Episcopal schools and classical-model Christian high schools. He taught Math and 20th Century American Literature part-time at St. Edwards University for 10 years. He taught full-time at Regents School of Austin from 1999-2012, serving as Math-Science Department Chair for eight years. He continues to teach on a part time basis at Regents serving as the Director of the Laser Optics Lab. He is the author of many science textbooks that I invite you to explore further on the Novare website.